How pharmacies, drug makers, PBMs and health plans are benefiting from your Rx benefits!

A closer look at branded drug reimbursements and drug prices.

It is easy to point fingers at rising drug prices, it is much harder to point at the drivers of that growth. To understand drug prices, one needs to understand how the drug value chain works, from the drug manufacturer to the patient. This value chain is an incredibly complex flow with many parties involved. Here is my take on explaining how the reimbursement of drugs work and who is making money along the way. There is a lot of nuance to this topic and will have to leave out quite a bit of detail here. To set some focus, I will only look at brand drugs that are distributed via a retail pharmacy. This is the bulk of the $500bn drug sales in the US every year. But there are also other value chains worth looking at, such as generic drugs & physician-administered drugs (for example like many cancer medications). However, they deserve a dedicated analysis, as the margin captured by the different players differs quite a lot.

Follow the pill

Let's get started and let us first have a look at this overview chart - don't get scared! We will unpack it step by step.

The first flow to understand is how the drug product is distributed from the drug manufacturer to the patient. In general, drug manufacturers sell their drugs to a wholesaler and the wholesaler pays for the drugs a list price set by the drug manufacturer also called wholesale acquisition costs (WAC). The wholesaler then distributes the drug to the local pharmacies and restocks their supply. The pharmacy pays the wholesaler - usually with a small markup to the WAC - for the delivery of the drugs.

And then the patient buys the drugs, pays the pharmacy and we are done... Unfortunately, the last step is not what happens, unless the patient is willing to pay the “inflated” list cash price set by the pharmacy (called the U&C price - usual and customary price). Most patients have their prescriptions covered by insurance and will show their insurance benefits card (or a GoodRx voucher - which is a whole other story.).

Follow the money

As any good drug sale investigator (pun intended) knows: follow the cash. The reimbursement side is a bit more convoluted than following the pill because cash is flowing in all kinds of directions. Here are the most important ones:

Patient → Pharmacy - Copay/ Coinsurance: When the patient picks up their prescription, the pharmacy checks with the PBM the patient's coverage and collects the copay that is required for the drug.

PBM → Pharmacy - Negotiated Reimbursement Rate & Dispensing Fee: After collecting the copay/ coinsurance the pharmacy will get reimbursed from the PBM at a negotiated rate. In addition to the rate they usually charge a fixed dispensing fee to cover the pharmacist's work.

Payer → PBM - Reimbursement & Admin Fee: Now, the PBM gets reimbursed by the health plan for each drug. In addition, for each prescription claim, the PBM will receive a fee from the health plan - this can be a flat fee, but often is a percentage of the drug price. But if the PBM takes an admin fee, why aren’t health plans not just reimbursing the pharmacy directly? One reason they go through a PBM are so-called rebates.

Manufacturer → PBM - Rebates: As PBMs can concentrate demand for a drug, they can negotiate rebates with the drug manufacturer. Manufacturers agree on up to 30-50% kick-back to the PBM whenever they fill a prescription of one of their members. In return, they get a more preferred position on the formulary. For example, they get pushed into a lower tier, not having to get prior authorization or not getting excluded from the list of covered drugs. I would think that for drugs for conditions with alternative branded or generic drugs, PBMs can negotiate larger rebates than in less “competitive” conditions, because they will credibly be able to influence demand towards the branded drug through their formulary.

PBM → Payer - Rebate Share: Every time a patient buys a drug and the PBM gets a kickback from the drug manufacturer, the PBM passes through a good part of this kickback to the health plan. It is not transparent how much the PBM is passing through of the rebates - but it seems that these days most rebates are passed through. I’ve found numbers ranging from 71% to 98%.

Manufacturer → Patient - Copay support: Last but not least - health insurers are increasingly using tactics called “utilization management”, which should disincentivize people from choosing costly brand drugs. Drug manufacturers are responding to this with several strategies, including copay support payments, which are vouchers that can be redeemed by the patient to get their copayment reimbursed. If you want to learn more about other ways drug companies respond to utilization management strategies read my last post.

With all these cash flows in place, we can introduce the concept of a net price of a drug: It's the list price minus all the costs mentioned above, i.e. rebates, wholesaler margin, admin fees, dispensing fee & copay support.

Who makes what?

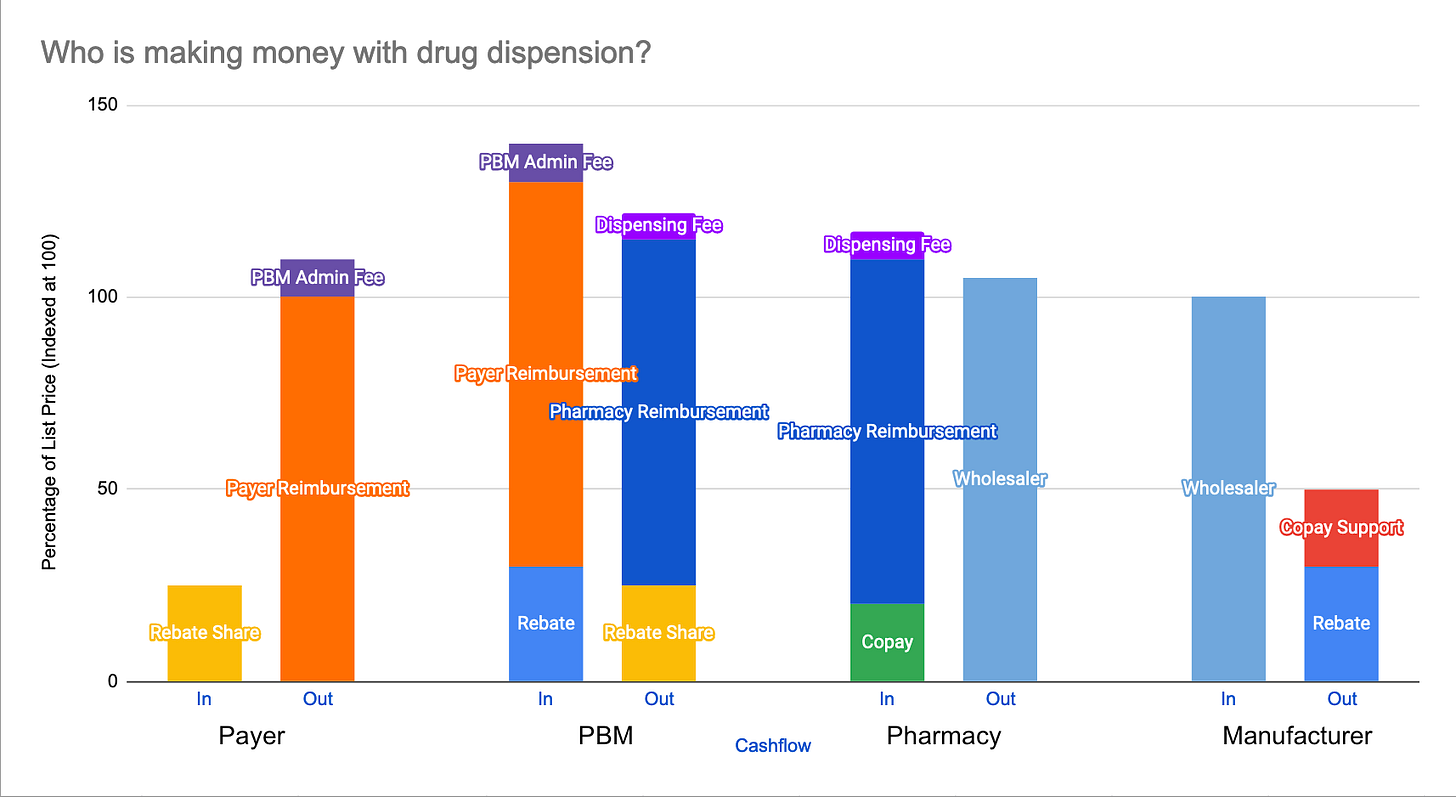

Now that we know how about the major cash flows in the drug value chain, it’s worth having a look at the gross margins for each party. I’ve illustrated the margins in this graph:

These numbers are more illustrative and should give you more of an idea of what the main drivers are than to show the actual margins. It is really hard to get the actual numbers right, as many underlying cash flows are not transparent. Most studies look at the overall net profits. Here is a great article that tries to estimate how much money is retained by each party.

Payer

The cash outflow from the payer is determined by the reimbursement amount and the admin fee minus any rebates the PBM is passing through. It is worth noting, that the reimbursement amount to the PBM depends directly on how much copay the health plan member needs to shoulder.

Pharmacy Benefit Manager

Three factors are driving the PBM’s margin:

Pharmacy Spread: Interestingly the amount the PBM reimburses the pharmacy is usually not disclosed to the payer and they usually take a higher price from the health plan for the drug than they pass on to the pharmacy.

Admin Fees: For each claim, the PBM gets an admin fee from the payer, usually the admin fee is a percentage of the claim value.

Retained Rebate: As mentioned above, the PBM retains a percentage share of the rebates they negotiated with the drug manufacturer. According to Drug Channels, the share of retained rebates has fallen quite a lot over the last few years.

Pharmacy

The relative margin retained by pharmacies for branded drugs is quite slim - unlike for generics. But as branded drugs are much more expensive, this can still be lucrative in absolute terms. However, pharmacies also have high fixed costs such as maintaining brick-and-mortar stores and employing state-licensed pharmacists. Filling prescriptions is a tough business, that's why when you go to CVS you are basically stepping into a high-margin product grocery store. On some drugs pharmacies even make a loss, but they hope they can compensate this through additional purchases through the customer.

Drug Manufacturer

The manufacturer realized price, i.e. the net price, is rarely the wholesale price. As you can see the actual gross margin for the drug manufacturer is depends on the rebates and copayment assistance they provide. Their ability to set a list price and how much rebate they have to provide depends a lot on the drug's “market power”, i.e. whether there are any substitutes and how effective the drug is in treating a certain condition.

Explaining the "Explosion in Drug Prices"

Understanding the margin drivers will help to understand a key trend in drug prices: Drug list prices have by far outpaced inflation, growing over 40% since 2014. But this fact only paints half of the picture - as we have established list prices are not the final price of a drug. There is research that net prices have grown much slower. But why do we observe this growing spread between list prices and net prices? The answer is: incentives...

High list prices with high rebates are in the interest of the health plan and the PBM, for several reasons:

Profits for PBMs: If we look at the profits above, PBMs make their profits through a percentage of the rebate they negotiate and a percentage of the value of the claim. The higher the list price the higher their income.

Digging the moat: The PBM market is quite consolidated, with three players processing more than 77% of all prescriptions in the US. If health plans don't want to pay inflated list prices they will need to go through some of the big three players (United's OptumRx, Cigna's ExpressScripts, CVS's Caremark). Concentrating so much demand will give them the power to negotiate deeper discounts. Smaller PBMs might not be of that much interest to the drug manufacturers. I would be very interested to hear how Mark Cuban's new PBM startup trying to break through this dynamic.

Silently reducing benefits: More than 50% of copays and coinsurance takes the published list price of the drug as reference and not the net price! This means that for higher list price drugs, the patient has to pay more out-of-pocket. This is a subtle way for health plans to take the benefits out of "pharmacy benefits".

I want to take a closer look at the last point: How much benefit is left in pharmacy benefits? Especially if you are on a high deductible health plan? Let's have a look at the unit costs. If rebates are 40-50% of the list price, co-insurance is between 10-33% and the PBM takes an admin fee between 3-5%. That means that PBM & health plans are keeping up to 83% of the list price and only cover the last 17%! If I haven't met my deductible and have to pay the drug in full, the plan even MAKES money through the rebates.

How could the drug value chain be disrupted?

So what are some alternatives to the existing web of payment flows and money that is falling of the wagon left and right? Here are some ideas worth exploring:

Point of sale rebates: Instead of having patients pay a co-pay based on the list price, rebates should be taken into account at the point of sales to calculate the fair share of copay. This is not a broadly adopted practice as this goes against the financial incentives of the payer and PBM.

Rethinking pharmacy benefits: It might make sense to think about pharmacy benefits more comprehensively - the same trend we see shifting from fee-for-service to value-based care for medical services, could also be applied to drugs. Instead of compensating drug manufacturers for each pill, one could design reimbursements based on a certain condition and drug treatment outcome. In the end, the right drugs can be a huge cost saver as they can prevent acute conditions and related hospitalizations.

Cost-plus pharmacy - What if one could completely disrupt the complicated web of inflated list prices and subsequent rebates and back-office haggling? Could there be a pharmacy that contracts directly with the drug manufacturer to sell a drug at an agreeable price for the manufacturer, plus a certain percentage for distribution? This could cut out a lot of the overhead. In his newest venture, CostPlusDrugs Mark Cuban is giving this approach a try - they are currently focused on generics, where manufacturing prices are relatively easy to assess (as generics don’t have to absorb the R&D overhead that branded drugs need to do). Let's see how they roll…

Let me know if you have more thoughts and ideas! Reach me at janfelix@substack.com or find me on Twitter @jfschneidr

Recently discovered this blog and love how clearly this very complex topic is laid out

Pharmaceutical product movement, contractual relationships, and financial flow are quite complex.

This webinar titled “Strategies to Address Rising Pharmacy Costs” includes some interesting graphics depicting these flows and relationships. See the graphics starting at 14:00 in this video: https://youtu.be/sr0RgHcX_no?t=840