Part II: How to reduce health care costs?

A review of cost containment strategies for employer-sponsored health plans

The pressure is on! The current economic climate is not only forcing overvalued startups to cut their costs. These days many businesses are reviewing their expenses to stay afloat. One of the largest expense items here are labor costs, particularly health care benefits. Coming out of the pandemic, many groups are hit with 10-40% rate increases, which CFOs across the country cannot ignore anymore.

So after we looked in Part I at the different ways companies can finance their benefits, let's look at all the tools available to employers to reduce their overall benefit costs.

In this article, want to avoid the prevalent trap of anecdotal savings. "Measure X has saved $1 million here, activity Y saved $500k there". There are plenty of anecdotes where a single initiative has yielded considerable absolute savings. But how generalizable are these strategies? I think it is worth taking a step back and looking at benefits costs from a high level and how they are breaking down.

Non-claims costs

Administrative expenses include everything required to set up and administer a benefits plan. Depending on the type of funding, they are sometimes more and sometimes less obvious. For example, in a self-funding arrangement, the administrative expenses include the TPA fee, the benefits consultant fee, and the PBM fee. In a fully-insured model, the administrative costs are included in the insurance premium. My take on this is that even though 25% of healthcare costs are administrative, this is not a huge opportunity to optimize. The TPA and benefits consultant business is pretty competitive. In fact, the focus on administrative sticker prices has potentially eroded the quality of administrative services.

Risk premiums: As mentioned in the last part, handing over risk to someone else usually comes at a cost. Here I am not talking about the expected claims cost - it is evident that a less healthy population has to pay a higher premium than a healthier population. But a group pays an additional premium if their risk is less predictable or measurable. Insurers will always assume the worst about you if you cannot prove them otherwise.

Claims-related costs

Price: This is the average cost for a specific procedure or an episode. There are major differences in the rates for a certain procedure, and provider rates are often not correlated to quality. A key strategy for employers is to obtain better rates.

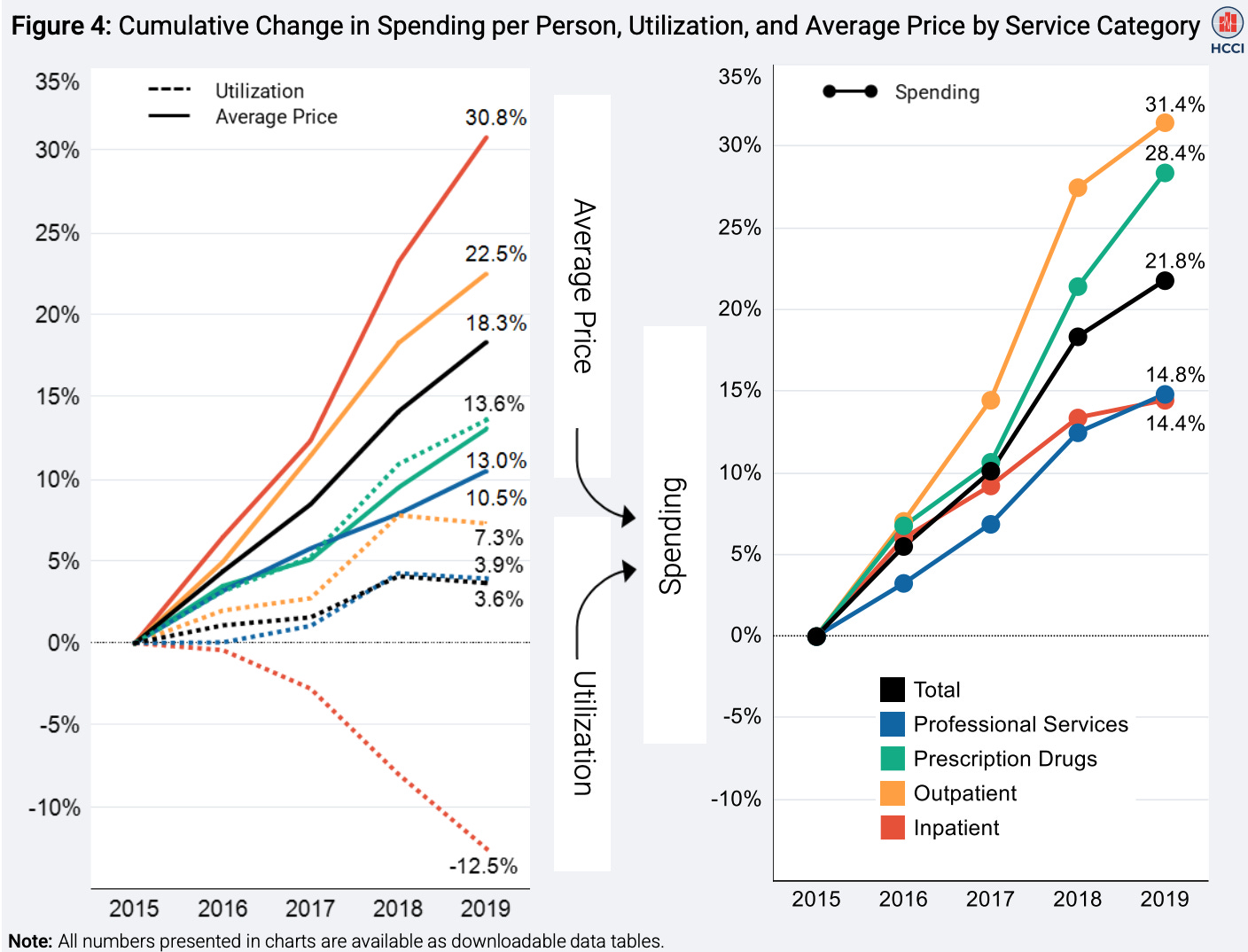

Quantity/ Utilization: Many cost containment efforts have focussed on unnecessary or avoidable utilization, like ER visits and elective surgeries. However, it's worth looking at the data to determine what is actually impacting rising costs. This interesting report shows how much of health care cost increases are driven by higher prices, not more utilization (see chart below).

Share of claims paid: The last important lever for costs is how much of the claim costs are even paid by the health plan. Several factors are going into this: the amount of cost-sharing with the employee, services that are included or not included (for example, fertility benefits, and acupuncture), and the number of rejected claims (for example, in case of fraud or lack of medical necessity).

Let's go through these buckets and see how payers are trying to address each of these.

Risk Premiums: Get a grasp on your risk

As discussed earlier, healthcare costs consist of the expected cost for claims and a risk premium if you decide to move some or all of the risk to someone else. For fully-insured companies, this is usually a 25% markup on expected claims (assuming an 80% medical-loss-ratio/ MLR, and for stop-loss, this is a 30-40% markup (assuming an MLR of 60-70%). Basic economic theory tells us that the more volatile your expected risk is, the higher your risk premium. Therefore, employers can try to reduce the volatility of expected risk.

More accurate predictions through better data: The first way to reduce the risk premium is to improve your expected claims prediction accuracy. A more precise prediction minimizes the uncertainty of the risk an insurer has to underwrite. Suppose an insurer gets proof that all group employees are healthy and don't have cancer or other costly conditions. In that case, they will offer a cheaper risk premium than if they only get limited information. The most important source of this proof is by reviewing claims data. However, claims data is often unavailable - especially for fully-insured employers; the employer usually only gets aggregated reports. A typical hack is to web-scrape claims data from insurance portals or to use health questionnaires. However, you will need consent and collaboration from each employee to hand over their data.

Pooling risk (reducing volatility) - Captives, MEWAs, PEOs: The basic idea of insurance is to leverage the law of large numbers - the more people you cover, the more predictable the risk will become. An insurer would be much happier to take on the risk for a group of 1,000 people, where they get $10m in premiums a year and have a 95% certainty of a $1m claim vs. insuring a group of 10 people, where they get $100k premiums in a year, but have a 5% risk for a $1m claim. Thus small employers are trying to pool their risk with other employers to save on risk premiums. Several options exist: In a captive arrangement, multiple employers contribute to a shared pool of funds, which will act as a buffer between the self-funded claim expenses and when the stop loss carrier kicks in. For example, an employer will pay for any claims up to $50k, from $50k to $250k the captive will cover the claim and after $250k the stop-loss carrier will take over. Similar arrangements are MEWAs (multi-employer welfare arrangements), where an employer association creates a health plan with a joint risk pool that a stop-loss carrier will insure. Another advantage of risk pools is the better negotiating power for both reinsurance rates and provider contracts. Owning more patient volume can improve costs. This fact is also used by professional employment organizations (PEO), a third way for employers to pool their risk. PEOs are co-employment arrangements where the PEO will take care of everything related to payroll, HR, and benefits administration. The PEO combines the workforce from several smaller employers and purchases group insurance for all their customers. Through their larger size, they can offer the insurance at lower rates, and often are the only way for small organizations to avoid insuring their employees through the small-group ACA marketplace.

Price: Avoid paying inflated prices

There are two common strategies to address provider rates. 1) Exploit price differences between providers and send members to cheaper doctors and 2) send them to the same doctors but try to get more favorable rates.

Improve provider competition through member steering

One of the most shocking facts about the US health system is how much variance in price and quality there is and how uncorrelated they are. Prices for very standard procedures can vary a lot. For example, a colonoscopy can range from $1,000 to $4,000, and an EKG can be $200 or $3,000 depending on the facility. Health plans have long tried various methods to exploit these price differences. Here are some common strategies to steer members to cost-effective providers:

Exclude coverage: The most effective way to avoid paying for costly services are hard coverage restrictions. Health plans can decide not to cover costs for particular services or providers. Narrow networks have proven to yield significant savings. While this is an effective strategy, many people dislike these restrictions, as they can disrupt the continuity of care if employees change health plans. Also, most people get their doctor recommendations through their friends or primary care doctors, which can be frustrating if their insurance network does not cover them.

Utilization management: Because hard restrictions are so unpopular, payers came up with many soft restrictions: prior authorizations, mandatory second opinions, primary care referrals, etc.. These are all ways to double-check medical necessity and quality of the approach before a member can go ahead with a specific drug or procedure! But be aware - providers and pharma companies are fighting back against these restrictions, and they have become an outright bureaucratic war with the member caught in the middle.

Virtual-first HMOs: This approach became more popular with the rise of virtual care - in a virtual care HMO, a patient will need to obtain a referral from a virtual doctor before seeing a specialist. The idea is that a virtual care visit is not as much of a burden as an in-person primary care visit. The virtual care team can quickly determine whether a specialist visit is necessary and refer to a cost-effective provider.

Financial incentives: Since price transparency rules kicked into effect, payers are now trying to make the price difference more evident to their members. Health plans waive copays to members for visiting preferred providers or give them lower or higher copays based on the cost-effectiveness of providers.

Soft nudges & concierge care navigation: A prevalent approach over the last years has been concierge care navigation, i.e., assisting members with finding a doctor and setting up appointments. Examples include text-based care navigation services, nurse hotlines, and free virtual care visits. Many employers have adopted this approach as care navigation: a) does not require many changes to the plan, b) does not add any restrictions, and c) can even be sold to employees as an extra service. People like to follow the path of least resistance, and there is so much friction in making appointments that care navigators can nudge people in the right direction. However, the onus is on the employee to find and make use of these services. As many people find their doctors online or through their friends and family, members often don't engage with this service and go directly to the doctor they want to see.

Get better rates

The second approach is to obtain better rates with provider groups. Often this depends on the willingness of the provider group to negotiate. Since many providers have built regional market power, they are not always willing to do that. However, here are some strategies:

Single case agreements: Single case agreements are one-off negotiations if a member needs to see an out-of-network doctor before their visit. The price transparency rules have given payers more tools to prepare for these negotiations and obtain a better bargaining position.

Bundled payments & direct contracts: In these arrangements, employers negotiate special rates upfront with their preferred providers for certain procedures or procedure bundles.

Reference-based pricing: A new trend to pay providers is to only reimburse providers based on the Medicare benchmark rate, for example, 170% of the amount that Medicare would pay. However, this puts patients at risk for balance billing, i.e., the healthcare provider might charge the patient the amount not paid by the carrier.

Medical tourism: If you cannot find reasonable rates in the US, many other countries around the world offer similar, if not sometimes better, quality of care at a much lower price. For example, an IVF treatment in Germany costs $3,000 - $5,000 vs. the average price of $15,000 - $30,000 in the US. Some employers now include medical holidays in their benefit plans to get lower rates.

Import drugs: Sometimes people don't want to travel abroad, but they can have the drug come to them. In 2020 the FDA and HHS relaxed rules around importing drugs from Canada. Those drugs are essentially the same as those purchased in the US and manufactured by the same companies, but they are often much cheaper. Companies like Sharx help employers procure drugs outside the traditional PBM route and realize cost savings.

… and the 1001 one-off things

There are several other, more minor ways to reduce prices and waste: i.e., use mail-order pharmacies, choose the right setting for physician-administered drugs (they are much cheaper if they are done at home rather than in a facility), etc., etc. A key challenge for these solutions it that they are usually only effective on a case-by-case basis. Health plans have to identify these cost saving opportunities and make a timely intervention, but doing these smaller, one-off opportunities can add up.

Reduce share of paid claims: Avoid paying in the first place

This is a very popular way of handling benefit costs - just don't pay for it or find somebody else to take on the risk. Here are a few popular options:

Shift risk to member: Shifting some of the risks to the member makes sense from a principal-agent perspective and aligns incentives. Making members pay a copay will incentivize them not to abuse their plan by seeking unnecessary care. Employers hoped that high deductible health plans (HDHPs) would lead to more shopping behavior in their members. However, this has not proven to be the case. They have only led to people postponing much-needed preventative care and, in the end, just shifted more of the costs to the members. In most cases, a member does not meet the deductible and has to foot the bill for their medical expenses alone. Basically, HDHPs are a reduction of health care benefits. Sweetening these plans with tax-favorable HSA accounts does not change this fact. The graph below shows how employers have embraced HDHPs and slowly shifted costs to the member (instead of increasing premiums, which would be a more obvious shift of costs).

Shift risk to provider: Another way of dealing with risk is by pushing it to the provider. This could be a win-win situation. The employer sets a fixed price for a specific episode, and the provider will get that amount regardless of the resources required to care for the patient. The more efficiently the provider treats the patient, the more money the provider can make. The provider is in the best position to do so, as doctors should decide what is clinically necessary and not payers. However, capitated models and payment bundles have yet to take off in the commercial sector. The main reason for this: providers tend to make more money billing fee-for-service than taking on the risk for outcomes. Why would you want to cannibalize your profitable business? There are also plenty of other obstacles, such as risk aversion, admin challenges and benchmarks (discussed further at the end).

Shift risk to another payer: If you cannot push the risk to the member or provider, you might find another payer to foot the bill. There are a few - not always very ethical - practices to shift costs to other payers. The first example is members with chronic kidney disease. After 30 months in dialysis, they qualify for Medicare, and Medicare will be responsible for their care - getting them to Medicare right at the 30 months mark instead of waiting longer can yield significant cost savings. Another strategy addresses high-cost employees that have left the company and qualify for COBRA. If they are on a self-funded plan, it might be beneficial for the employer (and the employee) to move them onto an individual marketplace plan. Even the premiums for a rich platinum plan can be much cheaper than the employer paying for medical care. The third method is to make your benefits unattractive for certain high-utilizing members so they will self-select to seek coverage elsewhere. This strategy includes removing certain high-cost specialty drugs from the formulary so the beneficiary will opt to get covered by their spouse's plan or find a more suitable individual plan. Last, there are cases where the payer should not pay out a claim because they are the secondary payer. Common examples are medical claims related to work accidents, which should be covered by workers comp insurance, or car accidents, which could be covered by liability insurance of the liable party. It is important for the plans to catch these situations and reject paying the claim.

Reject claims: It is estimated that 25% of all medical bills contain errors, and in most cases, these errors favor the hospital system that sent the bills. Payers must implement appropriate systems to catch errors and dispute them in time to avoid overpaying. This area of claims processing, called FWA (fraud, waste & abuse), tries to catch anything from upcoding (i.e., charging for a higher level of service that the provider did not deliver) to duplicate claims and unnecessary medical and billing inconsistencies.

Utilization: Address avoidable events and remediate them if they occur

Avoiding unnecessary care and improving the overall health of their population is an important area for health plans. It is also a weired one: shouldn’t this be the task of the physician? In theory yes, but adverse incentives and differences in quality push health plans into action. Here are three levers for reducing costs through improving outcomes:

Better primary care & improved access to care: The site of care matters significantly when it comes to cost: a primary care office visit is cheaper than an urgent care, which greatly beats the emergency room. In addition, primary care visits cost much less than specialist visits. Good primary care can take more tasks off the specialists' plates and should offer easy access to care to avoid urgent and emergency care. But changing primary care from a referral mill into more holistic care comes at a cost. I recommend reading Kevin O'Leary's article on the economics of more comprehensive primary care.

Chronic care management: Unmanaged chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension lead to more expensive acute care down the road. Thus it is vital to ensure members are equipped with all the drugs, services, and devices necessary to manage their condition. There are plenty of digital-first vendors out there addressing a range of chronic conditions via continuous engagement and small but frequent interventions.

Navigate costly episodes better: 80% of health care costs are caused by 20% of members. Some episodes and conditions will always be expensive - think kidney care (check out Zach's blog on it), cancer, or spinal surgery. If the care team does not properly manage these episodes, they can easliy become a multiple of the initial estimated costs. This can be due to a miscommunication between the different specialists, a poor quality provider choice, or unnecessary procedures and tests.

There are plenty of other mechanisms for how better care can yield cost savings. If you are building something in this space - feel free to reach out. I would love to hear your approach. I am planning another article just on this space.

JF's Thoughts

As always, here are some final thoughts on all these cost-containment strategies:

Point-solution fatigue: You’ve seen that there are plenty of ways to address rising healthcare costs. There is no silver bullet. Implementing the right point solutions for the right population can feel like whack-a-mole. Depending on the specific employer population and geography, some strategies work better; others are less effective. Orchestrating all these solutions can be a daunting task, and it is not getting easier that there are now hundreds if not thousands of solutions trying to sell to employers, all with their very nuanced offerings: For example, some MSK solutions specialize in treating shoulder problems others focus only on lower back pain. There is definitely a need for a better “matching” solution that helps employers identify the right solutions for their population and connects them to their health plan, particularly for smaller health plans. The current consulting-heavy approach only makes financial sense for health plans/ employers with a large population.

Point solution sales: The previous point has ramifications for the pricing model of many digital health and points solutions. Because there are so many providers now, they will need to consider their pricing model carefully. A PEPM model often does not make financial sense for many small to medium size groups if they only have 2-3 cases in a year. These groups would be much more willing to pay and adopt these solutions if they come with a case-based/ value-based pricing model.

The role of cash pay: In my article, I have left out an important trend: direct-to-consumer cash pay. Several startups are building D2C medical brands and offering cash-pay doctor networks with transparent prices. GoodRx managed to establish an interesting business here for drugs. However, it is crucial to consider who cash pay is most useful for: people who are generally healthy and who have a high-cost-share plan. If a person does not expect to hit their deductible, cash pay is often cheaper (also for the employer, as they do not have to pay for the benefit). But this model very quickly crumbles for people with higher utilization, which usually causes the most costs. There are interesting opportunities to integrate cash pay into the payment model for the plan, i.e. have the health plan “cover” the cash pay. However, this may add additional complexity for the member that needs to be handled. Also, there is still the perception of people that health plans should cover their benefits and they resist paying cash.

Obstacles to value-based care: One last thought on VBC, which is finding more and more adoption in the Medicare world. However, we have yet to see many value-based care arrangements for commercial health plans. A major obstacle, besides provider hesitation, is the issue with benchmarks. Whether something is deemed valuable is usually measured against some benchmark. There are two main issues with benchmarks, though: 1) The "value-based" organization can influence the benchmark, and instead of creating value, they will just play a benchmark game. Great examples are PBM drug price rebates or provider chargemaster prices. Provider network carriers and PBMs optimized for percentage discounts but, at the same time, inflated the base price, so there were almost no total savings. 2) The second issue are benchmarks that are catching up too fast. Let's say a value-based organization realized savings in one year. Where should the benchmark be set for next year? At the old benchmark, the new spending level, or somewhere in between? It is a delicate balance because benchmarks catching up too fast can lead to adverse incentives where value-based organizations might only realize some of the value they could at a time.

Above, I've started to touch on some of the challenges with all these cost containment solutions, but there is more. Many health plans are not implementing everything they can do to reduce costs. But this is a topic for the next part of this series. Don't forget to subscribe and share if you have liked it.

Continue reading here for Part III.

I am always excited to chat with thought leaders in the benefits space. If you are a CFO, HR leader, benefits consultant, or broker, don’t hesitate to reach out - I would love to chat.

This is very good. I had been waiting for Part 2 - and it delivered.